As we celebrate Black History Month and the vast contributions of African Americans to this country, let’s not forget the struggles and inequities that continue to this day. For one, higher education has a long history of excluding and underserving students who are not White, male, or affluent. After the end of slavery, states and the federal government continued to operate separate and unequal systems of higher education and provided support to colleges and universities that explicitly discriminated against students based on race and other characteristics. Although civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr. advocated for poor people regardless of race, they also fought for policy to specifically right the wrongs of racial injustice.

As we celebrate Black History Month and the vast contributions of African Americans to this country, let’s not forget the struggles and inequities that continue to this day. For one, higher education has a long history of excluding and underserving students who are not White, male, or affluent. After the end of slavery, states and the federal government continued to operate separate and unequal systems of higher education and provided support to colleges and universities that explicitly discriminated against students based on race and other characteristics. Although civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr. advocated for poor people regardless of race, they also fought for policy to specifically right the wrongs of racial injustice.

While some of Dr. King’s most popular quotes have been used to justify using race-neutral or colorblind policies, he in fact supported race-conscious policies such as reparations, which, even when paid, he argued, would amount to far less than “any computation based on two centuries of unpaid wages and accumulated interest.” Advancing racial justice in higher education, and beyond, requires atoning for the impact of historical and ongoing racism.

Using substitutions (or proxies) for race, such as income, cannot close gaps in opportunity and outcomes for students of color.

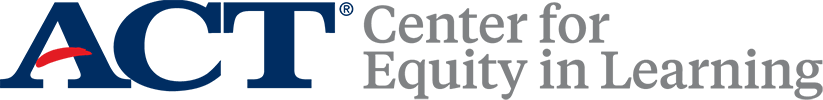

In a climate where race continues to be a difficult topic to grapple with, income is often the safe and convenient default measuring stick for higher education institutions. But in Ed Trust’s new report, Hard Truths, we make the argument that race-conscious policies are in fact necessary, because the playing field is so unlevel. For example, Black and White students and families with the same income often have vastly different experiences and circumstances that can affect educational and financial outcomes. For instance, White students from high SES backgrounds are nearly 2.8 times more likely to attend selective colleges than Black students from similar socioeconomic backgrounds. In all income groups, White students are at least 11 percentage points more likely to complete a college degree than Black students at four-year institutions (Table 1).

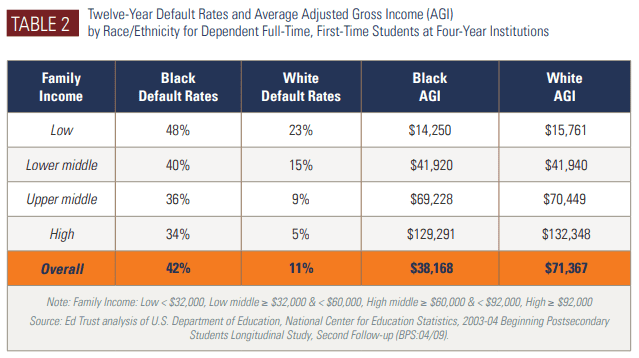

In addition to differences in completion, we also see differences between Black and White students’ (at four-year institutions) ability to pay back federal student loans (Table 2). Students who default on their loans face severe consequences, including wage garnishment, withheld tax refunds, denial of federal student aid, and more. Black students from the highest income families default at nearly seven times the rate of their White peers (34% vs. 5%). What is particularly alarming is that even among those Black students who are most likely to do well (i.e., high income, started full-time at a four-year college, and more likely to complete a degree), 1 in 3 of them still default on their student loans.

The Path Forward to Race-Conscious Higher Ed Policies

Despite the challenges that looming student debt can create for all students, earning a college degree still pays off economically. The problem is these social and economic benefits of higher education are not equitably distributed to people of different racial groups. That has to change. Here are just some of the strategies we recommend for advancing race-conscious policies:

- Colleges and universities should adopt a renewed commitment to affirmative action in higher education and use holistic admissions that include race as a factor.

- Colleges and universities should stop over-relying on traditional measures of “merit” and other admissions preferences that disadvantage students of color.

- Colleges and universities, states, and the federal government should provide more data that is disaggregated by race and ethnicity in higher education.

- The federal government should invest more in HBCUs, tribal colleges, and other minority-serving institutions (MSIs), and make sure enrollment-driven MSIs are truly serving students of color.

- The federal government should require accreditors to examine a college’s racial climate on campus.

Join us February 26 at 1:00 p.m. ET/12:00 p.m. CT for a joint Twitter chat with The Education Trust on the role and significance of HBCUs in Black student success. Find us using #HBCUFORWARD.

Tiffany Jones directs the higher education policy team at The Education Trust, where she promotes legislation to improve access, affordability, and success for low-income students and students of color. Before joining Ed Trust, Tiffany led the higher ed work at the Southern Education Foundation and was a dean’s fellow at the Center for Urban Education at the University of Southern California, where she helped advance the equity scorecard in Minority-Serving Institutions and urban high schools.

A Michigan native, Tiffany holds a Ph.D. in Urban Education Policy from the University of Southern California, a master’s degree in Higher Education Administration from the University of Maryland, College Park, and a bachelor’s degree in Family Studies and English from Central Michigan University.

Andrew Nichols is senior director of higher education research and data analytics, where he helps develop a research agenda that identifies patterns and trends in college access, affordability, and success, with a keen focus on improving outcomes for underserved populations.

Prior to joining The Education Trust, Andrew served as the director for research and policy analysis at the Maryland Higher Education and previously worked at the Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education. He holds a Ph.D. in higher education administration from Pennsylvania State University, a master’s degree from the University of Southern California and a bachelor’s from Vanderbilt University.