By: Nycole Stawinoga, Program Manager, Research & Communications

I wasn’t supposed to be in the gifted program in grade school. My placement scores were considered “average” to “below-average,” so I was placed in regular classes year after year. When I was in fourth grade my mom thought I wasn’t being challenged enough in school, so she advocated for me to be placed in the school’s gifted program. It took several meetings and constant phone calls to my teacher, the school principal, and the school district until the school finally agreed to place me in the gifted program halfway through fourth grade. Before I switched classes, my mom was warned; I would likely struggle in the gifted program and shouldn’t expect to receive grades higher than Cs and Ds. What happened? The next quarter in school I received Bs. The following quarter—I received straight As. Once given the opportunity to participate in the gifted program, I excelled. Being in the gifted program in elementary school led to me taking advanced classes in middle, honors classes in high school, a high ACT score, and ultimately receiving merit-based college scholarships, getting accepted into graduate school, and having a successful career. What I didn’t realize as a nine-year old, was the level of privilege that helped get me into the gifted program.

Educators, advocates, and policymakers often discuss the wide achievement gaps that exist in education. Data from ACT’s Condition of College and Career Readiness 2017 found “underserved students lag far behind their peers when it comes to college and career readiness.” What is often not discussed, though, is the gap in gifted education—something that can increase inequity in education if not resolved. Recently, Thomas B. Fordham Institute released a report, “Is There a Gifted Gap? Gifted Education in High-Poverty Schools,” that analyzes the gap in gifted education in the U.S. Overall, the report found 41,448 schools in the U.S. have gifted programs and 2.3 million elementary and middle school students participate in gifted programs. The good news is the report found overall, schools offer gifted programs at similar rates, even if the demographics of the student body are different On average low- and high-poverty schools were just as likely to offer gifted-programs. And 64.5 percent of low-poverty schools, 69.2 percent of middle-poverty schools, and 69.1 percent of high-poverty schools offered gifted and talented programs. When digging into the data on race and ethnicity, the report finds the percentage of minority students in a school does not have a significant effect on how likely the school is to provide gifted education.

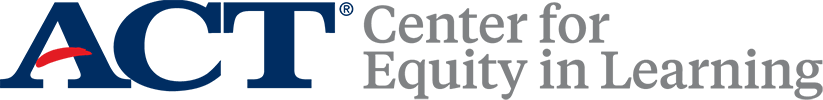

The gaps the report did uncover are gaps in who participates in gifted education. Students in low-poverty schools (12.4 percent) are twice as likely to participate in gifted education programs as students in high-poverty schools (6.1 percent).

*Figure 6 Graphic. “Is There a Gifted Gap? Gifted Education in High-poverty schools,” Thomas B. Fordham Institute (12).

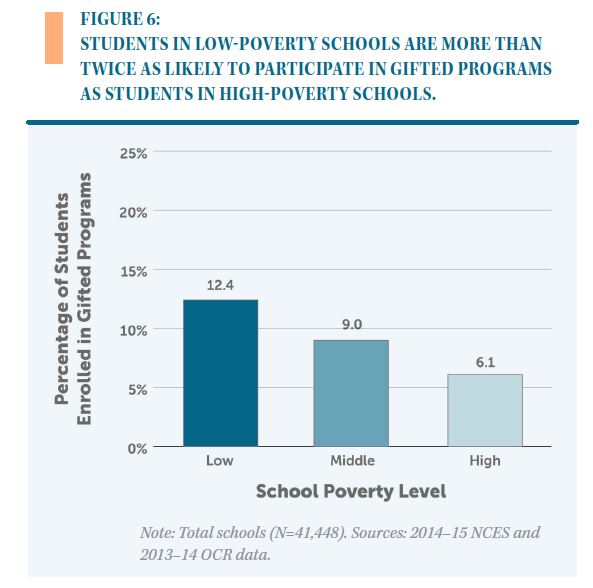

More so, nationally, in all schools with gifted programs, “Black and Hispanic students participate in gifted programs at lower rates than their Asian and white peers (12).”

*Figure 7 Graphic. “Is There a Gifted Gap? Gifted Education in High-poverty schools,” Thomas B. Fordham Institute (13).

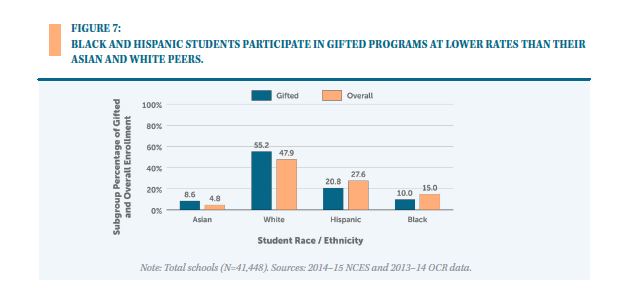

In high-poverty schools Black and Hispanic students are statistically underrepresented in gifted programs.

*Figure 8 Graphic. “Is There a Gifted Gap? Gifted Education in High-poverty schools,” Thomas B. Fordham Institute (13).

According to the report’s foreword by Chester E. Finn, Jr and Amber M. Northern, “When high-achieving or high-potential poor and minority students have less access to gifted education than their peers, the existence of such programs may actually worsen inequalities (4).” The Fordham Institute’s report makes three key policy recommendations it believes will shrink the gifted education gap. These include:

- Assess all students in every school to determine if they qualify for gifted programs.

- Rather than identifying the highest achievers across a school district for gifted programs, identify the highest achievers at each school.

- Counter unconscious bias among teachers and work toward employing a more diverse teaching staff.

If we want to decrease inequity in education, this report makes clear that we must create and support policy ensuring students from low-income families and/or minority students who achieve high academic results or have the potential to flourish academically are in gifted education programs. Failing to do so, will not only prevent thousands, if not millions, of underserved students from achieving their academic potential, but it will exacerbate the already large equity gaps that exist in education, and add additional barriers that underserved students will need to overcome to achieve higher education and workplace success. I was lucky and privileged to have the opportunity to be in a gifted education program. This changed my life. Race, ethnicity, income, and other factors should not be a barrier for students to participate in gifted education programs. There is still a lot of work still to do to make this reality.