Most Americans believe there are benefits to receiving a college education and earning a college degree. This is a viewpoint supported by research. Data from the National Center for Education Statistic’s (NCES) 2017 Condition of Education (COE) report shows young adults with a bachelor’s degree earn more, on average, and have higher employment rates than young adults who only completed high school. With such concrete benefits from attaining a bachelor’s degree, it’s imperative that every student, regardless of their background, have access to a quality college education and the resources to help them graduate on time.

The good news is that in 2015, a majority of high school graduates immediately enrolled in college (69 percent)—an increase from 63 percent in 2000. However, when the NCES looks more closely at the data, it’s evident that large inequities continue to exist for underserved learners. For example, college enrollment rates for students from high-income families are much higher (83 percent) than rates for those from low- and middle-income families (63 percent for each).

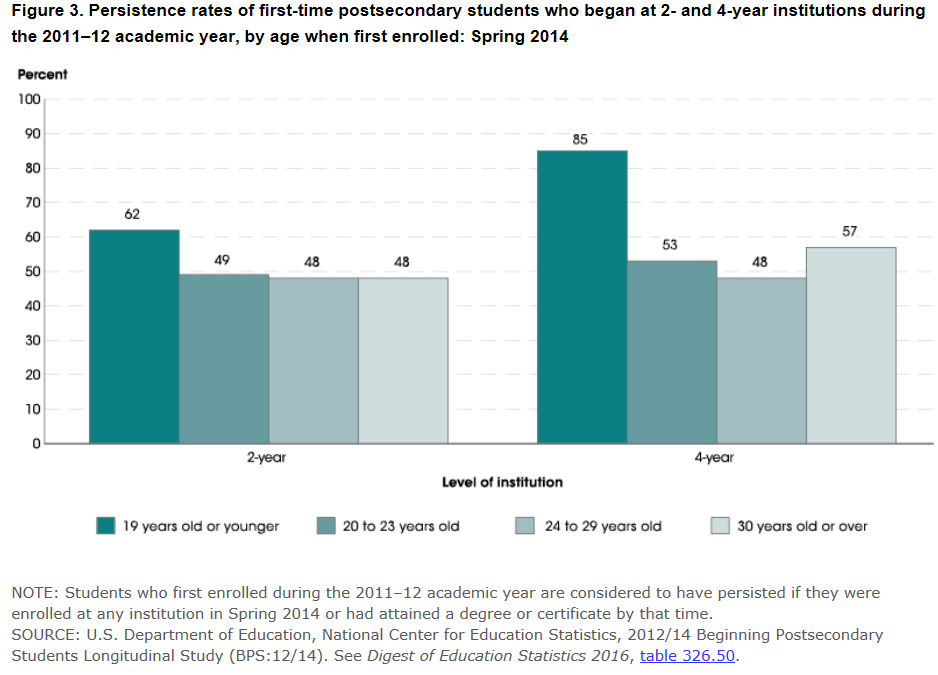

Access to affordable, high quality higher education for all students is merely the first step toward achieving educational equity. Too realize the full benefits from attending college, students must also remain or persist in college and earn their degree. NCES’s 2017 COE report, describes the results of a longitudinal study it conducted from 2011-12 to 2012-13. The study tracked a group of first-time college students over a three year period to measure their persistence rates. The results are telling.

Overall, 80 percent of all first-time college students who began at a four-year college or university in 2011–12 were still enrolled or had attained a certificate or degree three years later. Similar to the data on college enrollment, a closer look at the data by NCES, shines a light on the large inequities that continue to exist for underserved learners. At four-year colleges and universities, 90 percent of Asian and 82 percent of White first-time college students remained enrolled in college or had graduated after three years. On the other hand, only 64 percent of American Indian/Alaska Native, 69 percent of Black, and 79 percent of Hispanic first-time college students persisted in college after three years.

2017 Condition of Education Report, National Center for Education Statistics

Older, “non-traditional” first-time college students also had lower persistence rates than those traditionally viewed as “typical” first-time 18 or 19 year old college students who enroll immediately after graduating high school. NCES’s report found when students first enroll in college at 19 years of age or younger, they have higher persistence rates at both two- and four-year colleges than students who begin college after 20 years of age.

2017 Condition of Education Report, National Center for Education Statistics

Overall, the results from the NCES study provide valuable data on who is enrolling in college, where they are enrolling, and the characteristics of students who are persisting or who are still enrolled in or have graduated from college after three years. As ACT and other education leaders work to close achievement gaps, data such as these and on other groups of underserved learners are necessary to identify inequities that exist and to inform the conversation as we work to develop solutions to end inequity in education.