Work Learn Earn Presentation

Walk onto any college campus in the United States and chances are that nearly every college student is either working or knows someone who is working to help pay their way through school. With the cost of college tuition, books, housing, and other living expenses rising faster than the cost of inflation, working and learning, or attending school and working at the same time, has become increasingly common.

There are approximately 14 million working learners, or individuals who are simultaneously working and going to school in the U.S.ii

1This brief is based off of the report Who Does Work Work For? Understanding Equity in Working Learner College and Career Success. Sarah Blanchard Kyte, Ph.D., July 2017

While previous generations of college students may have graduated college with little to no debt by working to pay their way through school, today’s high tuition and stagnant wage levels make that nearly impossible to do.iii

Despite higher costs of living, most Americans still believe there is a benefit to attending college and attaining a degree.i And, there is a benefit. Those with a college degree generally have better jobs and earn more over their lifetimes. But, to afford that college degree, today’s college students often must work to supplement living expenses or financial aid packages that either don’t cover the full cost of tuition and basic living expenses, or include student loans that must be paid back.

Given that it is increasingly common for college students to work and attend school at the same time, helping students integrate and balance the demands of working and learning has become an education and economic issue that is at the forefront of thousands of college students’ lives and the lives of their families each and every day. With this in mind, a few questions surface: Who are today’s working learners? How often are they working? Are there benefits to working and learning? What about challenges? Does working during college affect all students equally?

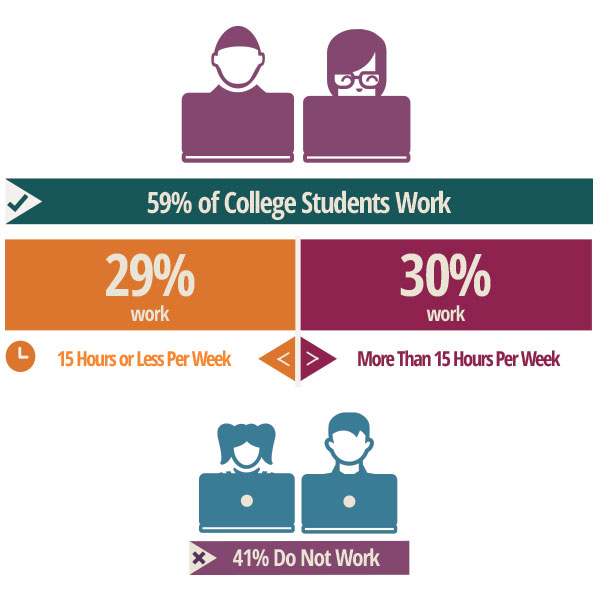

Nearly 60 percent of college students work during their freshman year of college. More specifically, before students even complete their first year of college:

While working learners include students from a range of backgrounds and academic characteristics, working learners who work more than 15 hours each week are represented among certain groups at a higher rate than they are represented among college freshman more generally. These include:

- first-generation college students

- students from low-income families

- students with a grade point average below 3.5

- students whose highest high school math course was less than pre-calculus

- students attending a college with a minimally selective admissions process

This means that underserved learners, those who have experienced education inequity before even entering college, are the college students who are working the most. Demanding work schedules mean significantly less time to attend class, study, sleep, socialize, and spend time with their families compared to working learners who work 15 hours per week or less or don’t work at all.

Twice as many college students working more than 15 hours each week believe their job has limited their class schedule, limited the classes they can take, and has negatively affected their grades compared to college students working fewer hours.

For students from low-income families, a demanding work schedule with less study time means that after two years, they have lower GPAs compared to their classmates who work less demanding schedules. Low-income working learners who work more than 15 hours each week are also less likely to graduate on time—likely resulting in an increased risk of not completing college.

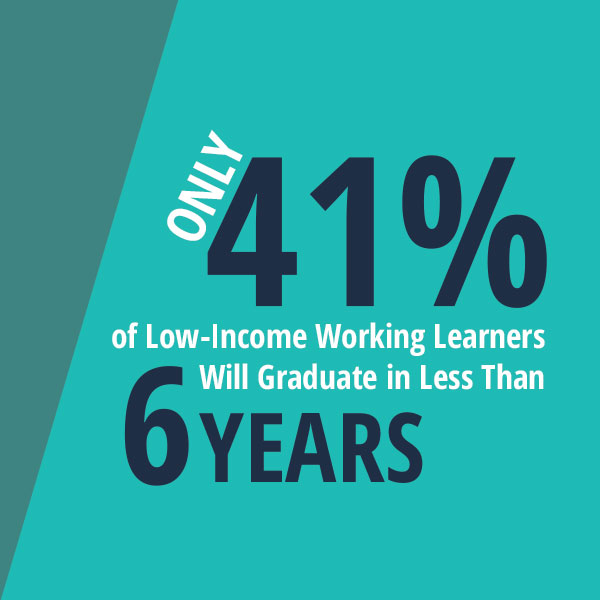

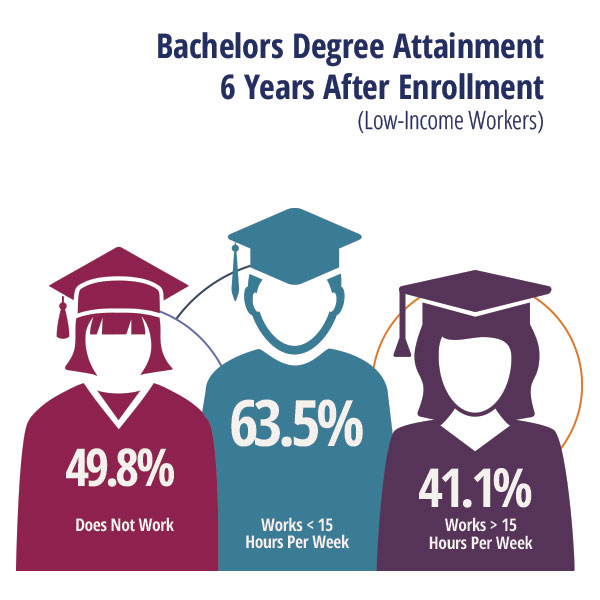

What’s more, only 41.1 percent of low-income working learners who worked more than 15 hours each week had earned a bachelor’s degree within six years—a rate significantly lower than other college students.

Working learners clearly face a number of challenges as they try to juggle demanding work and class schedules week in and week out, but there are also a few benefits to working while in college. After two years of college, low-income working learners who stick to a work schedule of 15 hours per week or less progress through college and graduate with a bachelor’s degree at a higher rate than those who have higher workloads.

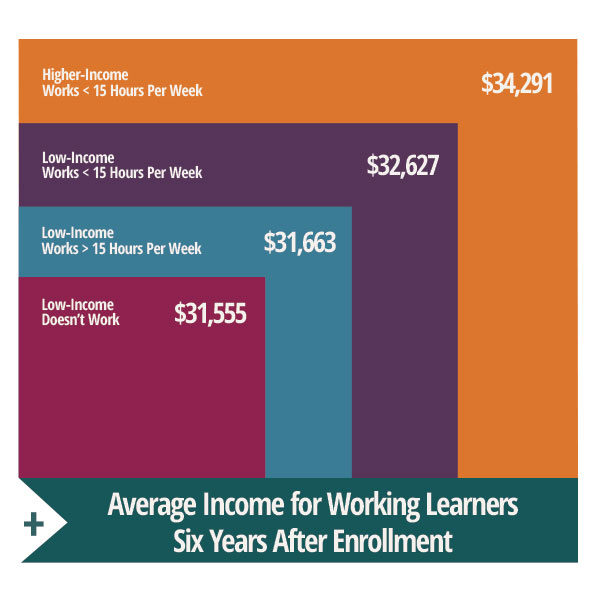

After graduating college, early in their careers, college students from low-income families who work a moderate number of hours have incomes similar to college students from higher-income families who also work a moderate number of hours each week.

The average income for these same low-income working learners is also slightly higher than for those who either work more demanding schedules or don’t work in college at all.

To achieve educational equity, we must improve support for working learners, particularly underserved working learners, with policies and practices that minimize the disadvantages they face to earning a college degree, by:

- Raising wages for hourly and service workers

- Expanding Financial Aid

- Making college more affordable

There are benefits to holding a job in college when students have a limited workload. Therefore, policies must financially support underserved college students and allow them to maintain a work schedule that doesn’t overextend them or get in the way of their long-term academic or career success.

Policy alone, however, will not end inequity in higher education for underserved working learners. Internal practices colleges and universities can adopt to better support working learners include:

- adopting more holistic advising approaches that account for both coursework and paid work

- bridging the divide between campus career centers and financial aid offices to help place students into jobs with long-term career benefits

By treating paid work as an extension of coursework when advising students, university faculty and career advisors can help working learners maintain a balanced workload and class schedule that leads to academic and career success. Furthermore, departmental collaboration within colleges and universities will only help to maximize the effectiveness of the resources available to better support working learners.

Earning a college degree is virtually a necessity to being able to compete for a high paying job in today’s economy. Millions of college students work and go to school each and every day in the U.S. to earn that coveted degree. While working in college is standard for students from all different backgrounds, underserved learners are overrepresented among working learners—balancing more demanding work schedules and facing greater academic challenges compared to other college students. To improve achievement and career outcomes for working learners and ultimately achieve equity in higher education, working learners must have access to affordable higher education opportunities and resources to support them as they navigate their way through college as working college students.

i) New America. (2017). In Depth Varying Degrees. Washington D.C.

ii) Carnevale, A.P., Smith, N., Melton, M., & Price, E. W. (2015). Learning While Earning: The New Normal. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University.

iii) Blanchard Kyte, Sarah, Ph.D. (2017). Equity in Working and Learning Among U.S. Adults: Are There Differences in Opportunities, Supports, and Returns?: ACT Center for Equity in Learning.